This is the second in a series of comparing the bike share programs in Columbus, Ohio, and Carmel, Ind.

Carmel Bike Share, Carmel, Indiana

The bike share program in Carmel, Ind., is operated by Zagster, a company which offers more than 200 programs in 35 states. The setup is much different than other bike shares I’ve used over the years so I was very interested in trying out this program. Instead of a kiosk and a bike docking station used by programs in many major metropolitan cities, the Zagster setup consists of a set of locked bikes at a station with an information board explaining the program. Payments and locking mechanisms are controlled through a smartphone app.

Program Summary

To use this type of bike share program, you need to install the Zagster app on your mobile device. If you don’t have the ability to download apps, you can arrange for payments and unlock bikes using text messages.

There are currently three payment choices:

- Annual membership at $30 a year which includes free trips which are under an hour. After the first hour, users are charged $3 per hour up to $24 per ride.

- Monthly membership at $15 per month which includes free trips which are under an hour. After the first hour, users are charged $3 per hour up to $24 per ride.

- Pay-as-you-go which costs $1.50 every 30 minutes up to $24 per ride.

In all cases, if a bike is kept for more than 24 hours, users will be charged an over time fee of $24.

To use a specific bike, you find the bike’s number from the bike and enter it into the app. If the bike is available, you will be given an unlock code. This code is entered into the key pad on the bike. Once the bike is unlocked, you can remove it from the docking station. To return the bike to a station, you just park it and press and hold the lock button on the keypad until the light flashes. Then you find the orange tab on the lock and slide it down and place the docking cable into the port on the lock. Finally you tap “End Ride” in the Zagster app.

At the station in Carmel, there were two different types of bikes available: a “cruiser” and a “trike.” Both bikes had baskets.

My experience

Having only used the more traditional type of bike share program, I was a little hesitant in trying this one out. Fortunately this time, I was able to do so with my partner which was a great help and expanded our experience. For example, I had no problem downloading and using the app. But while my partner was able to download it, he could not get the app to give him the code to unlock the bike. So he used the text option to get the code which worked great. If he had not been with me, I probably would not have been able to see how the text function worked.

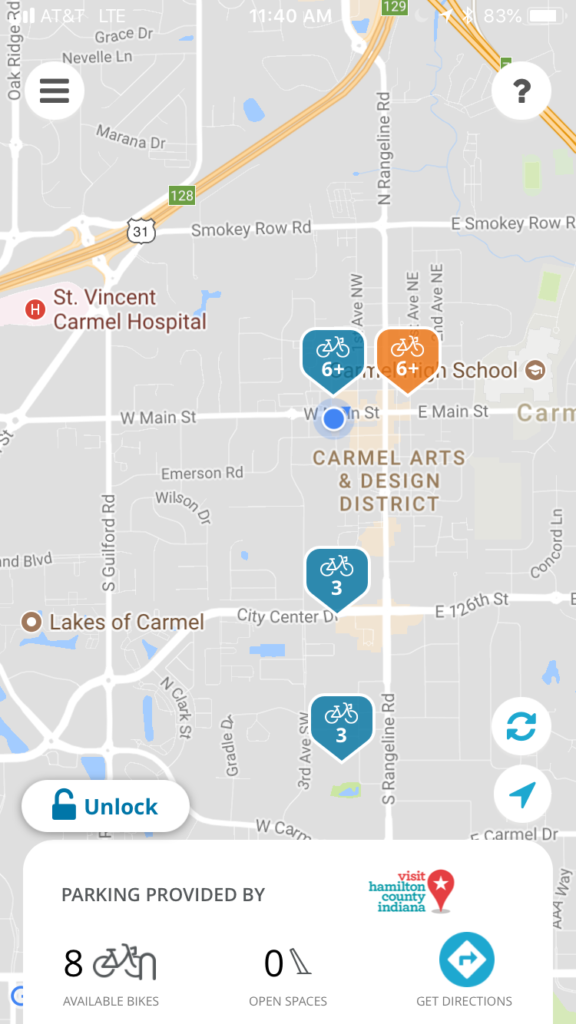

So we installed the app and went to a bike share station in the Carmel Arts & Design District. This is an example of how the map on the app looked for that area. You can see it is showing eight available bikes and no open spaces at the station colored orange which was on Main street and to the east of us. We also checked the one closer to us, and it showed seven available bikes with five open spaces.

One thing we discovered right away was even though there were several bikes shown as available and several bikes locked into the dock, once we went to the screen to choose the bike and get the code, fewer bikes were actually available. I was wondering if this is because some of the bikes were still “checked out” on rides and only temporarily locked there by the users.

We eventually found two bikes, each of us bought a ride, and received an unlock code. The locking and unlocking process wasn’t obvious to us, but we did manage to eventually figure it out. Below is a photo showing how the bike is connected to the station.

Once we got going, I was looking forward to a long ride since we didn’t have to worry about returning a bike in a specific amount of time. We could keep it out for a couple hours and just pay the total cost for that time. The station where we picked up the bike was right along the Monon Trail so we began biking south along that path. It didn’t take long before I realized the bike I had was making a strange and annoying noise. I tried recording it – you can watch it by clicking this link:Â Â Bike Noise Video

So there was no way I could stand listening to that for two hours. Fortunately there was another station a little way down the path so we stopped there for me to return the bike, pay the $1.50, and pick another bike that I hoped would offer a more silent ride. After getting it unlocked and starting off again down the trail, I was happy to find out this one made no noises. After our ride we went back to the Arts & Design District and returned the bikes.

While the access process took a little getting used to and we had that noise issue not only that time but also the next time we used the service, overall the experience was still positive. I would definitely use the Carmel Bike Share program again. Here’s my list of pros and cons from the perspective of a visitor, not a resident:

Pros

- The best aspect of this system for me is that bikes do not have to be returned to a dock within a specific amount of time. This offers a lot more flexibility for users in choosing their routes.

- The cost was very reasonable.

- Bikes can be locked anywhere so users can stop along their ride to eat, shop, or explore. We saw users along the trail who had done this and were eating at restaurants along the trail.

- Once I got a bike that worked, it was easy to ride.

Cons

- The main issue for me was that twice we had problems with the bikes. While the cost to pay for another ride wasn’t much, it was annoying having to return the bike to a station and hope out of the few available bikes there, I would get one that would not make a noise.

- The actual number of available bikes seems to be less than what appears in the docking station and on the app.

- The setup and process to getting a bike takes some time to figure out.

- A person cannot check out multiple bikes. So if you are riding with someone they need to get a bike on their own.

In comparing the two systems, I definitely prefer the Zagster bike share program. Yes there were some maintenance issues with the bikes and figuring out the process took some time. But not having to worry about getting a bike back to a station in 30 minutes made it definitely worth putting up with those other things. Also, the cost was very reasonable.