Many people might be surprised to find out there is a virtual real estate market and have had a hard time understanding how someone could pay money for something that you can't physically touch like virtual land. Before visiting virtual worlds myself, I would not have believed people would pay money for something like that. It was only after spending time in places like Second Life that I began to see the value people found in having a virtual space and virtual objects. Over the years I've watched as this value increased to create a billion dollar virtual goods industry – reported by TechCrunch to have reached $2.3 billion by the end of 2011.

But while the virtual goods market has increased, the virtual land market, at least in places like Second Life, has seemed to follow a trend similar to that of the physical real estate market in the U.S. In both places, land values have dropped and the amount of vacant and abandoned land has increased resulting in a surplus of properties. Because of the similarities I've seen in the offline and online markets and their affects on communities, I thought it would be interesting to look at a comparison of the physical and virtual markets and explore movements towards recovery.

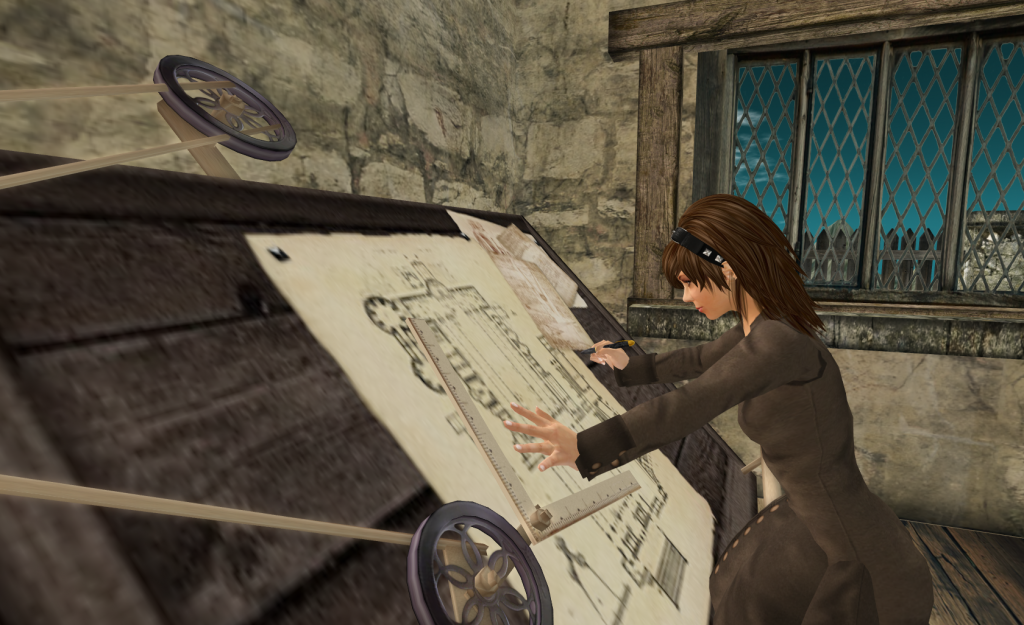

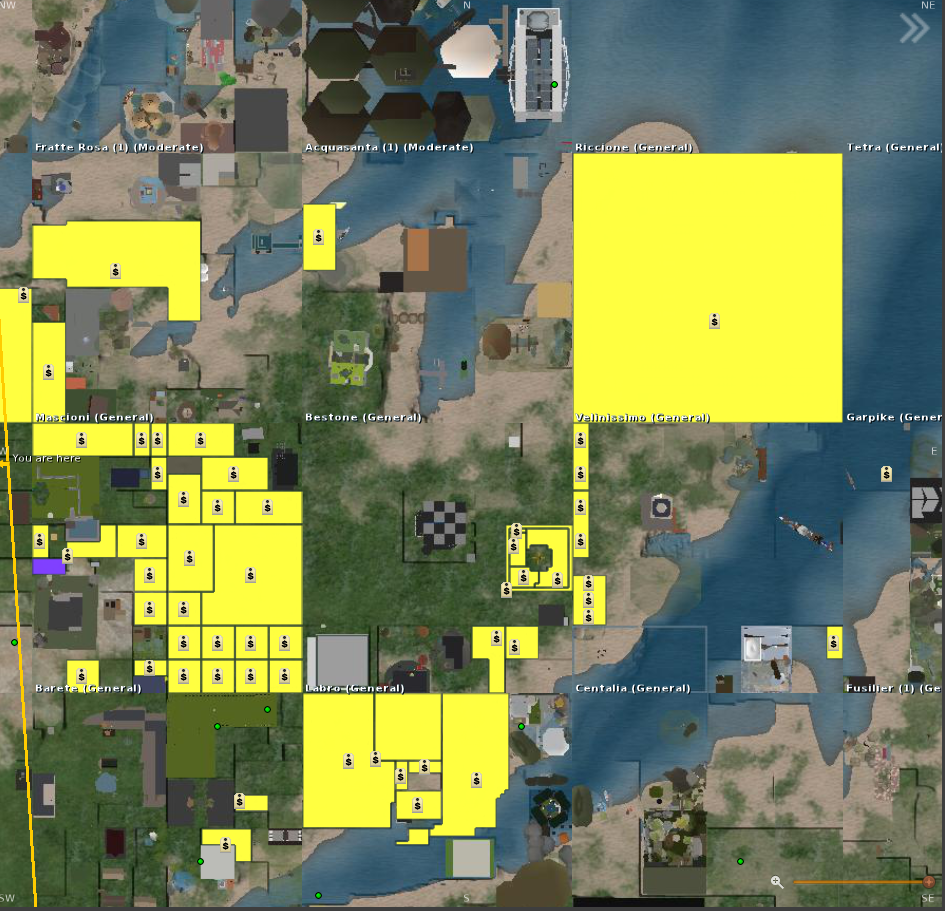

To get an idea of the amount of land available for sale in Second Life, I took a screenshot showing the large number of parcels for sale in an area of Second Life. Each dollar sign indicates a parcel on the market. (The green dots represent people who are visiting a space.)

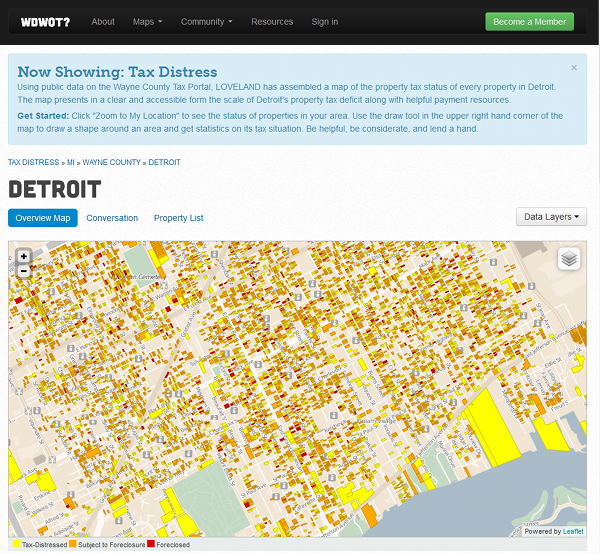

In most offline communities the number of vacant and abandoned parcels would not appear to be as large as what is seen in the virtual land market in Second Life. But there is one place where it does seem close – Detroit. Below is a screen shot of a website called Why Don't We Own This by Loveland Technologies showing the number of foreclosed or tax-distressed parcels in an area of Detroit.

To better understand the performance of the virtual land market, we need to know how land is handled in a place like Second Life and what drives people to buy it. The world of Second Life is made up of many islands of virtual land also referred to as sims or regions. Each sim measures 256 m by 256 m. People enter the world in an avatar form which is a digital representation of themselves that they can use to explore the world. The basic land, sky, and ocean are provided by the company hosting the world of Second Life. Everything else that someone would see there was created by users. This can include plants, buildings, and other objects placed to enhance the user experience. People can also build upon or change the ground, water, and sky features with objects they create.

However, all of these objects take up space in the world and use up computer resources. So Linden Lab, the company hosting Second Life, assesses a fee to users who want to leave their objects permanently displayed on a parcel of land. And because it would be chaos for people to just randomly leave things everywhere, they control where people can place their items by requiring people to own the land where their objects are displayed. At a basic level, you can think of it as renting storage space on a server where you are allowed to store your files. The only difference here is that in Second Life your files can be displayed as 3D objects and you and others can visit them in avatar form. I suppose it could also be compared to renting a storage unit where you can keep your physical possessions. Although one difference is that you are only allowed to take out objects or files in their entirety if you created them – you are not allowed to take something out of Second Life's system just because you purchased it.

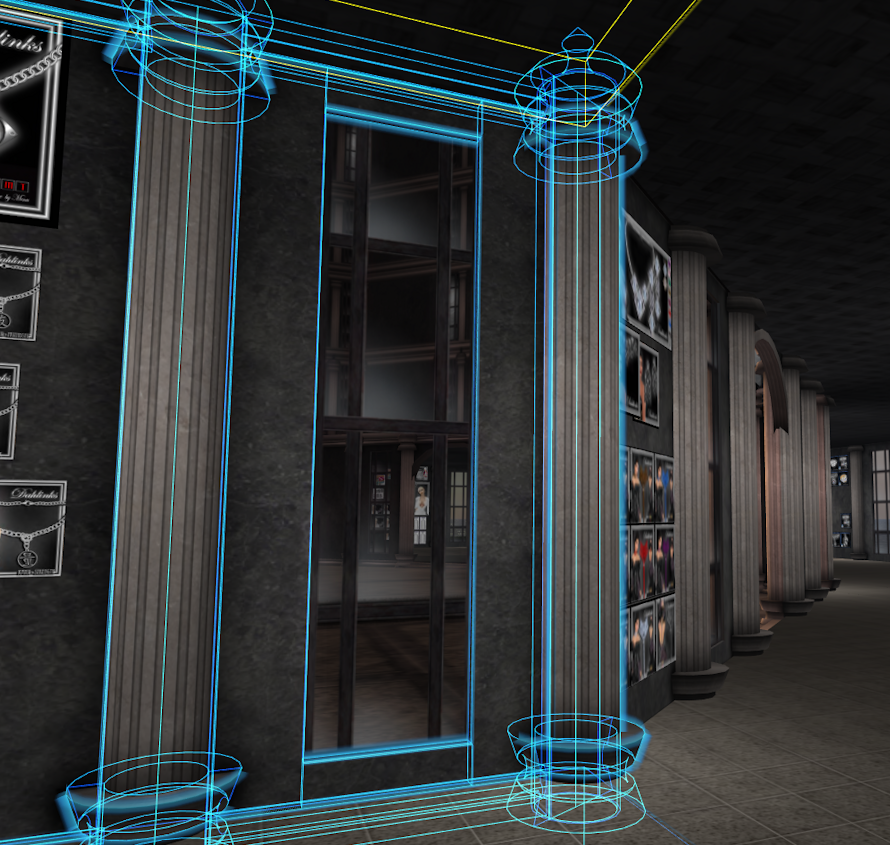

Anyway, here's how the costs are assessed in the virtual world. Because the fees are dependent on the resources used, Linden Lab first sets a limit on the number of objects, which are called prims (a prim is a basic building unit), allowed on a full sim to 15,000. To get an idea of how prims are incorporated into objects you can look at the photo below taken inside of a building in Second Life. The highlighting outlines each prim used to make this building.

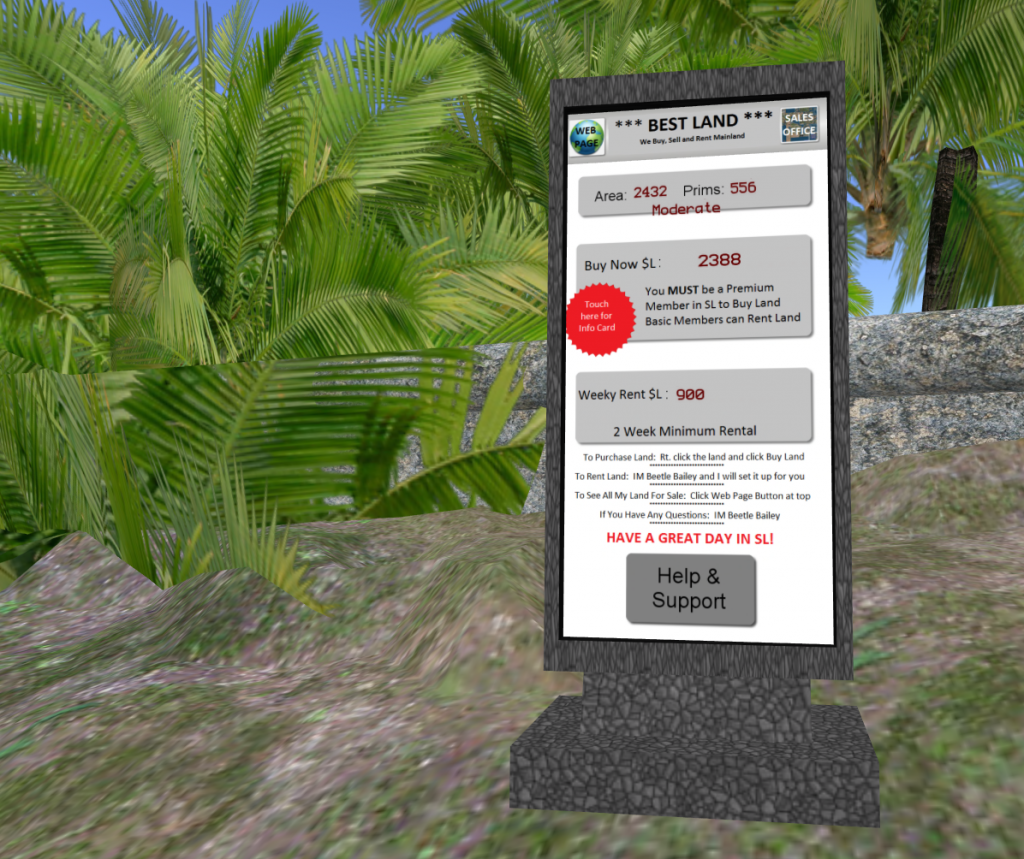

Then Linden Lab offers users a choice between two different types of land for display of their items: Mainland and Private Islands. Mainland is a large group of islands or sims available to anyone to purchase and then subdivide and resell. Below is a detailed map showing parcels for sale in an area of mainland in Second Life. For reference, the large, yellow square is a full sim measuring 256 m by 256 m. Before the fall of the land market, mainland islands sold by Linden Lab through auction could cost about $1,000.

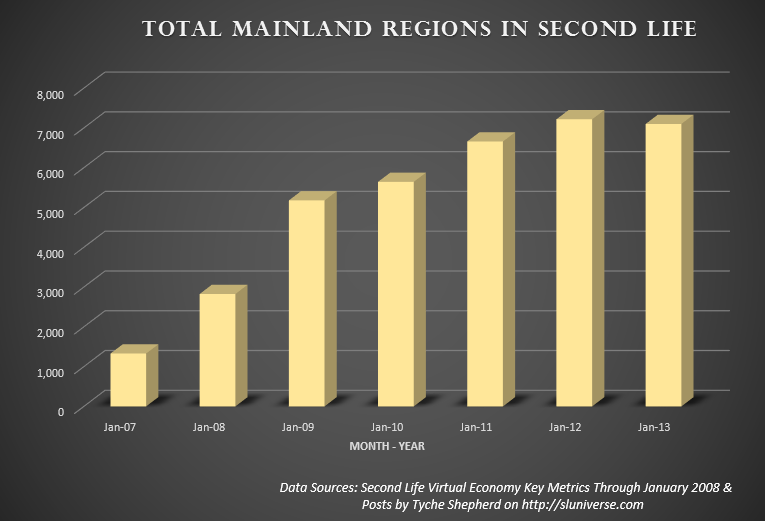

Back then, the lowest resale cost was a few dollars per square meter. Today the cheapest resale cost is $0.17 per square meter. This difference is simply a reflection of what happens when supply exceeds demand. It almost sounds exactly like what happened to many developers in the physical real estate market who had invested in subdividing land and were left with vacant lots and no buyers after the market fell. Many of those developers went bankrupt and lost the land to the bank. In Second Life, when owners abandon their parcels, they return to the ownership of Linden Lab. Below are a few statistics of the status of mainland in Second Life (these numbers come from Tyche Shepherd). Because of the amount of vacant and abandoned land, the amount of mainland has remained close to the same for some time at just over 7,000 regions with no new regions being added – there's just no demand to justify the creation of new land.

- 46.5% of mainland is owned by Linden Lab

- 10.6% to 11.6% of mainland is abandoned (assuming not yet returned to Linden Lab)

- 7,121 Mainland sims in total (that's about 467 million square meters of land)

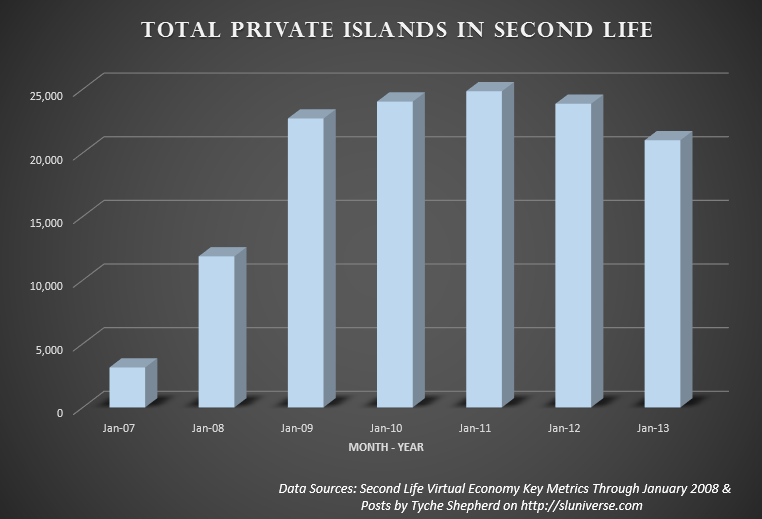

The alternative land choice available to users is a private region or island. These are available in full sim size only and can be sold or subdivided, but ownership cannot be transferred at the parcel level. Private islands vary in cost based on how many objects you can place on the land because Linden Lab does offer full private regions with different resource allotments. A full island allowing 15,000 prims costs $1,000 to purchase, a "Homestead" island allowing 3750 prims costs $375, and an Openspace island allowing 750 prims costs $250. You also have to own a full island to be able to purchase a Homestead or Openspace sim. In 2008, there were almost 27,000 private regions. Today there are about 20,700, and the number seems to be decreasing at a steady rate.

One question that some of you might be wondering, if you are not familiar with Second Life, is why would people abandon the land they bought? Why spend $1,000 for a private region then just let it go? The answer is in the fees Linden Lab charges for the use of the land you buy. These monthly costs, often referred to by users as "tier," can also be thought of as a type of rental charge for the resources used to store and display virtual objects. Tier varies depending on the size of the parcel. A full sim (65,536 sq meters) on mainland costs $195 a month while 512 sq meters costs $5 (512 sq meters of land is limited to 117 prims). A full private sim or region costs $295 a month. So just like in the offline world where you might have no mortgage yet still lose your property because you cannot afford the taxes so too in the virtual world. You might have been able to buy the land at one time, but usually it's the ongoing costs that cause you to give up your property. In the physical world it might be the real estate taxes, and in the virtual world it is the land use fees or tier.

People who have owned land in Second Life, including myself, have complained for many years that tier is too high. Many of us have said that people increasingly cannot afford land if tier is not reduced. And this seems to parallel exactly what happens in the offline world. People who cannot afford the taxes in a community complain and try to get them lowered. But while there is somewhat of a relationship in the physical world between the amount of taxes and the size of the parcel, other factors influence the rate. Real estate tax is set by government based on the school costs and cost to the government for providing services. It can only be reduced so much without cutting back on education or services or investment in assets. In the virtual world, the fees or tier are also needed to pay for services such as the hardware supporting the world, upgrading of software and features, and customer support. But a significant difference is that because the virtual world is owned and managed by a private company, fees also support profit – in the physical world, profit is never part of the equation for assessing taxes.

So for those of us facing high real estate taxes in our physical spaces, we can complain to our elected officials and demand taxes be reduced or frozen. But if they decide to cut or freeze our taxes, it will be by reducing services which we might not want to accept or which might cost us more in the long run. Of course we can move to a different community, but there are several down sides to this solution. Education and government services have a similar cost across the United States. Sure there might be some areas that save money because they don't have to deal with costs for handling winter weather or they have cheaper labor costs, but most people don't analyze city and school budgets and compare them to each other to figure out if the difference in tax rate is due to these factors which are actual cost savings or if they are due to a reduction in services. Uprooting your family and moving them across the country to find the most cost effective community in which to live is also a major challenge. This would require a significant investment of time and money along with the need to find a new job and perhaps if children are involved a search for a new school or daycare. Most of us just don't have that kind of mobility in our physical world so we are limited in our ability to move.

Government has tried to explore other methods of reducing the cost to live in a community. There are assistance programs for those who qualify and freezing of taxes for senior citizens. Based on a comment from one of my Facebook friends, it appears the U.K. might be trying to encourage people to downsize to a home that might be more affordable for them by assessing a fee on unused bedrooms in a home. Affordability of housing is and probably will be an ongoing challenge for communities.

In the virtual space, people have pointed out that some of the operation costs for hosting a virtual world have been reduced because of lower costs for the infrastructure so tier should be lowered to reflect this. But others have argued that fees cannot be lowered or profits will be lost. In the end, Linden Lab has not indicated in any way that tier will ever be reduced. So people who are upset with paying the level of "taxes" or tier have to make a decision between accepting the costs or moving to another virtual world. After all, Second Life is no longer the only virtual community out there.

But a downside to making that virtual move is that people can experience an "uprooting" similar to what they would feel from a move in the physical world because they are leaving their friends and community, but that is where the similarity ends. The time and investment needed to make a virtual move is significantly less than what it takes to move in the physical world. And there are usually no jobs or schools or other factors to have to worry about. People still risk the reduction in services by moving to a world with a lower cost, but it's much easier to research and explore what those reductions will be if any.

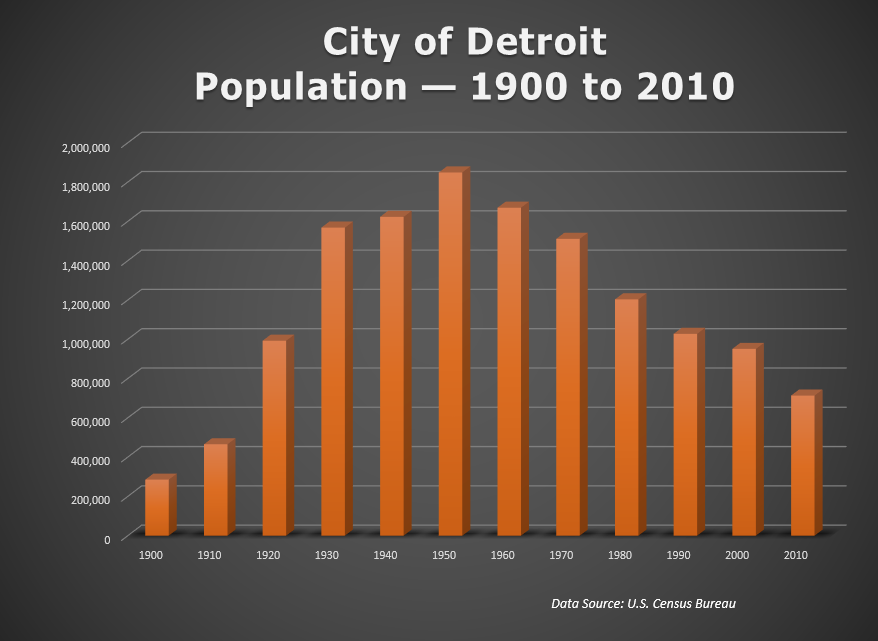

So let's finally look at what happens to a community when costs of land do not decrease, services decline, and the population becomes alienated from its caretakers. Again we will look at Detroit – in the last decade, this city has lost 25% of its population (see Wall Street Journal article). Some of the reasons cited for this loss are affordability (taxes and jobs) and a reduction in services. It almost becomes a viscious cycle because as people move out values fall, properties are abandoned, and taxes must be raised to offset losses. So many properties in Detroit were abandoned that some sections were even closed off. But as shocking as Detroit's current situation appears to be, it seems it has been steadily declining for decades. There's an interesting discussion about the causes here: The Reasons Behind Detroit’s Decline by Pete Saunders.

Those who follow the virtual land market in Second Life might see some similarities in that declining graph. And while the elements within the virtual and physical communities might be different and the downward trend not as long, people believe Second Life's land decline is caused by management issues that sound a lot like Detroit's: a refusal to discuss or address the decline and the cost of maintaining land, a focus on meeting the needs of one or two primary groups, and a lack of investment in the community to the point where people sense a feeling of neglect. And when I say this, I don't mean the company managing Second Life is actually neglecting the world. As a person working in government I am well aware of the essential work and effort that goes into operating a community – work that no one knows about or wants to know about. And I believe Linden Lab is taking care of all those operational duties much like a public works department works in the background to make sure a city keeps functioning. The neglect comes about because in addition to keeping the gears turning, a community needs nurturing to be successful.

Even if you think you are meeting the needs of the people, if the population thinks you are not, then you are not. For those of you who used to play Sim City it is kind of like the newsflash you would get telling you what the people in your city thought about the job you were doing. When they were unhappy, you would try to figure out what you could do next to change their opinion to one that was more positive. Well, unless you were the type who liked to inflict disasters and mayhem on your city just to see how bad it could get.

After 60 years, Detroit is now working hard to stop their decline. They are engaging the public and offering incentives to encourage people and business to move to their community knowing it can ultimately lead to lower costs for everyone as revenue increases. And they are no longer listening to only one industry – now everyone in the community has the potential to voice their ideas and opinions through online sites and public meetings and workshops like the one shown in the image below. The people who love and care about Detroit do not want it to slip into oblivion.

Those of us who love Second Life also do not want it to slip away, but we do not seem to have reached the point yet where the owners of the world have expressed any concern about the loss of land and investment. And we face a challenge somewhat different from people in places like Detroit. Those running our community do so to make a profit and they alone have ownership. In places like Detroit, the people own the community – in the end, they have the power to keep the lights on or turn them off and walk away. In Second Life, this decision is ultimately up to the company owning that world.

Perhaps the owners of Second Life are content to make as much money off the world as possible while allowing the decline to occur until expenditures exceed revenue. Then at that point, they just shut it all down and go on to their next thing. Or they might expect the decline to eventually stabilize and as long as they are still making an acceptable profit, they will be content to leave the world at that size. After all, not every community wants to become a metropolis. And some communities only want a demographic that can afford to "live" there.

Finally the other option is what Detroit has chosen – address the decline and determine a path to turn it around. And just as Detroit is investing significant effort now to accomplish growth, this option would also be the most work for Linden Lab. There are some who have suggested Linden Lab is pursuing this option by launching other potential revenue streams. And some have suggested imposing new fees unrelated to land. If these steps were taken, the company could choose to use new revenues to help meet costs of operating Second Life and still ensure profit while allowing for a reduction in tier. This is somewhat similar to a city adding new taxes or service fees or a city that works to attract a heavy sales tax or industrial base and uses the additional revenues to offset a reduction in taxes for residents. But if the company chooses to build a new revenue base, the key will be to diversify, because history shows relying on one group or industry or revenue stream eventually leads to a collapse. The video below is a trailer for a documentary about communities and the aftermath of this type of collapse.

As the young man points out in this video the "The soul of the city . . .are the people." So if Linden Lab chooses to follow Detroit's path, they need to also follow their example of engaging and informing the community and embracing the people because the people really are Second Life. Without them, there is only water, ground, and sky. And people cannot be expected to invest time and money in a community without knowing its plan for the future or feeling like they have a say in that future. As decades of emigration and our example of Detroit have shown, when people have no clear path to the future and lose faith in leadership on top of facing high costs, they will eventually seek out a new world and opportunities.

Thanks for this thoughtful piece on Second Life, and the life of Second Life, the persistence of virtual land. I thought your comparison to Detroit particularily telling, in that it highlighted similarities as well as differences between the virtual and "analog" worlds.

I wanted to add one difference, namely that, unlike Detroit, Second Life can deteriorate, indeed, Second Life can disappear, with no consequence for a neighboring area. Detroit, and any challenged geographic area, is embedded in a system of physical and market relationships such that it's decline challenges other areas, which have an incentive to support that area's recovery. Detroit is not going away. It will be there, either as a vibrant city or a struggling one.

Not so in Second Life, where places, even famous and popular places, disappear frequently. When these place disappear, they are gone. No decaying bridges, no blight on the landscape. They just go away, and I can not help but believe that being able to consider that the option of causing the entire Second Life world to go away colors Linden Lab's strategic conversations.

Again thanks for your thoughtful article,

Gjo Bing from Second Life

@Gjo – that’s a great comment. It definitely is an important difference that can affect the outcome as you point out.

Fascinating comparison of the two "worlds", thank you so much.

Excerpted with great pleasure for slum magazine.

Fascinating and thoughtful comparison of the two "worlds"; thank you so much.

Happily excerpted for SL readers of slum magazine.